The concept of passive beamforming topology may not be widely recognized, yet it is extensively utilized in the realm of RF technology.

For many years, directional antennas in radar applications dominated the scene. These antennas either had a fixed directivity or were rotated in a consistent pattern at a known rate, as illustrated in Figure 1. There were also antennas that could be repositioned as required, such as the large ones used in radio astronomy. Nevertheless, antennas with dynamically adjustable directivity were uncommon, except for expensive electronically steered antennas (ESA) primarily utilized in military radar systems.

Figure 1. This mobile radar antenna is mechanically steerable but only in a limited, pre-defined pattern. (Image: Wikipedia)

In recent years, the landscape has significantly shifted. Antennas capable of real-time redirection have become more prevalent, driven by mass-market consumer products like smartphones and their base stations. These applications demand an antenna system that can swiftly adjust its directional focus, surpassing the capabilities of mechanically steered systems.

The electronically steered antenna (ESA), also known as a phased-array or multiple-input/multiple-output (MIMO) antenna, is now experiencing widespread adoption. This article delves into the Butler matrix, a passive technique widely used for implementing an ESA, despite its relative obscurity. Such paradoxes are not uncommon in the complex and enigmatic world of RF signal processing, which often features unique devices and configurations unfamiliar to the broader realm of electronic engineering.

Essentials of electronically steered antennas

Q: What is the fundamental principle behind electronically steering an antenna’s directivity?

A: The concept has been well understood since the early days of wireless and optics. By employing a linear or two-dimensional array of antenna elements and precisely controlling the relative phase of the signal driving each element, constructive and destructive interference of electromagnetic energy occurs at different angles.

Q: How is electronic steering accomplished?

A: Implementing electronic steering is a sophisticated process, especially when dealing with signal frequencies in the hundreds of megahertz and tens of gigahertz range, where typical RF considerations and issues play a significant role. There are two primary methods to enable the dynamic adjustment and control of signal phasing, known as beamforming, to the antenna elements: active and passive.

Q: What is active beamforming?

A: An active beamforming network comprises power combiners/dividers, digitally controlled phase shifters, and attenuators. Such a network enables continuous beam sweeping, with the phase shifters and attenuators supporting broad bandwidth.

However, this technology comes with inherent drawbacks. The digitally controlled phase shifters and attenuators necessitate complex control circuitry, including digital-to-analog converters (DACs), analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), and logic-control circuits. The entire setup also demands significant power consumption. Effective heat dissipation and temperature-compensation circuits are essential to uphold stable circuit performance.

The Butler matrix as an alternative

Q: What serves as an alternative to active steering?

A: The Butler matrix, a passive beamforming network. Configured in an n × n N × N square with hybrid couplers and fixed-value phase shifters at internal junctions, the Butler matrix features n N input ports (beam ports) where power is applied and N n output ports (antenna elements) connected to n antenna elements.

The Butler matrix distributes power to the configured elements, introducing a progression of phase differences between elements; this results in the transmission beam aligning in the desired direction. When a signal is injected into one of the input connectors, it is evenly distributed to all output connectors with precise phase relationships.

Q: Up to this point, the focus has been on Butler matrices for transmission, but can they function for reception as well?

A: Indeed, the Butler matrix is a passive reciprocal network, functioning identically in both transmitting and receiving energy. In transmit mode, it delivers the full transmitter power to the beam, while in receive mode, it captures signals from each beam direction with the full antenna array gain. For simplicity, we will assume it is used as

Q: What is the size of the Butler matrix?

A: All Butler matrices feature equal input and output ports, with the number always being a power of two, ranging from 2 to 4, 8, 16, and beyond. If fewer ports are necessary, the unused ports must be terminated with matched loads to avoid unwanted reflections that could severely distort performance. The 64 × 64 size is commonly used in aircraft scanning applications; some fixed installations even extend to 128 × 128.

Matrix principles may not be readily apparent

Q: How does the Butler matrix operate?

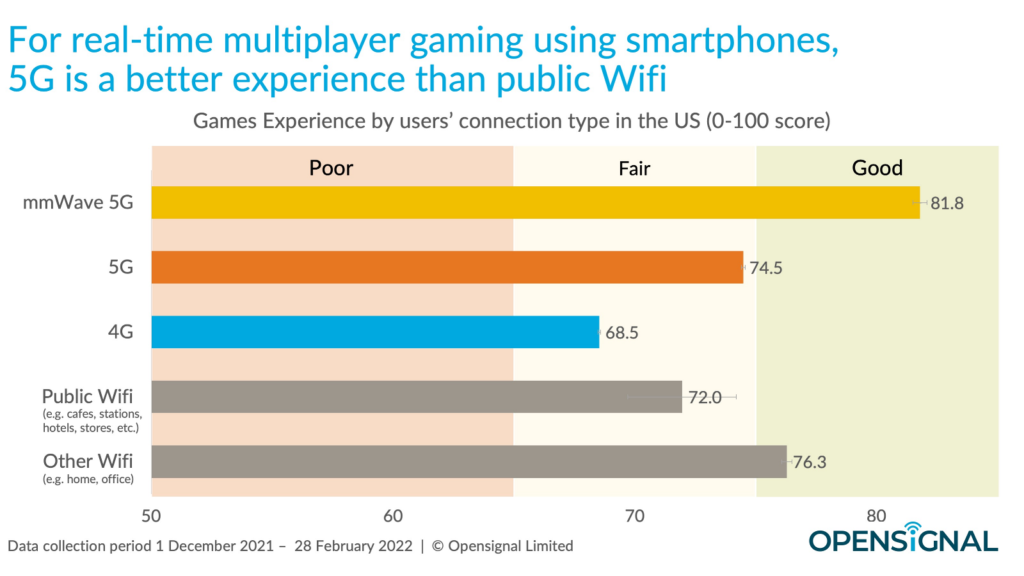

A: Beginning with the smallest Butler matrix, featuring just two inputs and two outputs, depicted in Figure 2. When a signal is injected into Port 1, it splits into two signals ideally at -3 dB amplitude with quadrature phase, while injecting a signal into Port 2 yields the same output but with mirrored phase. Consequently, it can feed a two-element antenna array and generate beams steered to the left and right, contingent on the feed port selection.

Figure 2. A 2 × 2 Butler matrix can cause the directivity of an antenna to skew off-axis either to the left or right. (Image: Wikipedia)

It is worth noting that the actual angular spread is influenced by factors such as antenna element spacing, frequency, and others.

Q: How about for higher-order matrices?

A: The next Butler matrix size, featuring four inputs and four outputs, as depicted in Figure 3. When a signal is fed into Port 1, each output is at -6 dB with a progressive phase shift of 45°. For inputs 2, 3, and 4, the phase shifts are 135°, 225°, and 315°, respectively. Notably, 225° is equivalent to -135°, and 315° is the same as -45°. This configuration generates two beams on either side from the center-path “boresight.”

Figure 3. A 4 × 4 Butler matrix offers more granularity in the off-axis directivity. (Image: Wikipedia)

For higher-order Butler matrices like 8 (seen in Figure 4), 16, and 32, the signal is divided with progressively lower amplitudes of -9 dB, -12 dB, and -15 dB, respectively, alongside smaller progressive phase shifts of 22.5°, 11.25°, 5.625°, and so forth. The number of generated beams always matches the order of the Butler matrix, x, with their directions becoming denser as the order increases.

Figure 4. An 8 × 8 Butler matrix has even more granularity in the off-axis directivity but at a significant increase in hardware complexity and component count. (Image: Wikipedia)

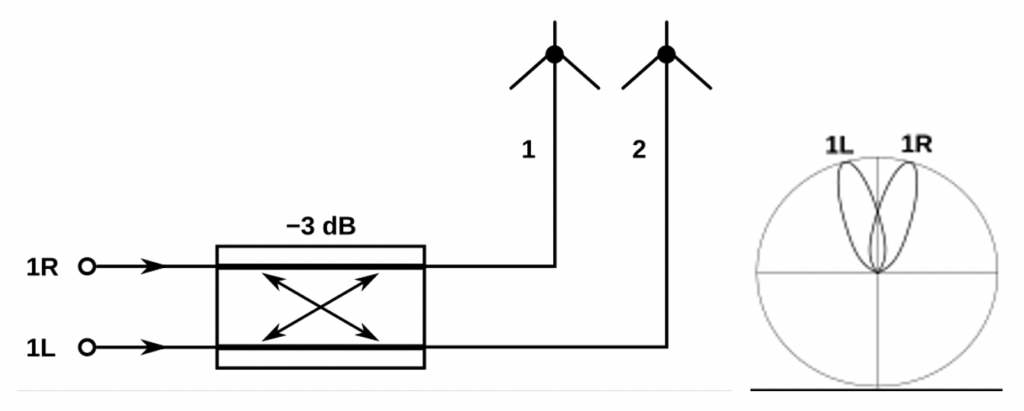

Q: What is the correlation between the input port receiving the signal and the output port pattern?

A: The phase table below (Figure 5) for a 4 × 4 Butler matrix elucidates this relationship.

Figure 5. This input/output table for a 4 × 4 Butler matrix shows the relationship between the input port, which is fed a signal (A1 through A4), and the relative phasing of the outputs (B1 through B4). (Image: Krytar)

Q: From the diagram, it seems that the phase shifters play a critical role — is this accurate?

A: In the realm of RF technology, every element holds significance. The 2 × 2-port Butler matrix does not utilize phase shifters except for the 90° hybrid. The 4 × 4 matrix incorporates two 45° phase shifters alongside the four hybrids, positioned between the hybrid levels. Moving to the 8 × 8 matrix, it incorporates 22.5° and 67.5° phase shifts between the first and second level, with 45° phase shifters between the second and third level. Higher-order matrices introduce progressively finer phase shifts.

The absolute performance, tolerance, and stability of these phase shifters are pivotal factors impacting overall performance.

Q: While I understand what a phase shifter is, can you clarify what a “hybrid” signifies in this context? The term seems to have varied interpretations.

A: Here, “hybrid” denotes “hybrid coupler.” A hybrid coupler serves as a specialized directional coupler that evenly divides an input signal between two output ports with 3-dB coupling. Depending on the design, the output signals can exhibit a phase difference of 90 degrees or 180 degrees.

Figure 6. The basic hybrid coupler divides the input into an in-phase and a quadrature signal. (Image: EverythingRF)